Tags: Decision-making, Wellbeing, Ethics Programme issues, Treatment of Employees

How to support employees in living up to the organisation’s ethical values in their day-to-day business activity remains the key challenge for business. An ethics function holds a vital role in making sure that ethics is part of all business operations and that the core values are embedded and reflected in the organisation’s culture.

Over the last 30 years, it has become the norm for organisations to encourage their staff to maintain high ethical standards of business practice. This stems from a growing consensus that firms must serve a social benefit if they are to earn a licence to operate. The challenge however, is how to best support employees in living up to the organisation’s ethical values in their day-to-day business activity.

The role of an ethics function

It is difficult to provide a general definition of the role and scope of the ethics function that would be applicable to all organisations. The operation of each organisation’s ethics function differs according to its internal structure and the sector in which it operates. Therefore, when considering the effective management of an ethics function, the foremost priority is to define a clear mandate, spelling out the function’s key responsibilities specific to a particular organisation. This is important as there is no one-size-fits-all approach to business ethics.

It is imperative to set the mandate of this function to go beyond compliance. By definition, business ethics begins where the law ends. It involves discretionary decision making and relies mainly on individual responsibility and voluntary commitment. Establishing a dedicated function for dealing with ethics will reinforce the company’s commitment. In particular, it communicates the idea that a compliance-based approach to rules and regulations is important but insufficient for empowering each employee and ensuring they feel responsible for promoting an ethical culture within their company. A question to ask: is compliance the ceiling you are aiming for, or the foundation which you are building on?

Generally, it is recognised that the ethics function holds a vital role in ensuring that ethics is part of all business operations and that the core values are embedded and reflected in the organisation’s culture. Its duty is to guide the implementation of the ethics programme which is often seen as a point of reference for employees wanting to raise concerns or ask questions when faced with an ethical dilemma. This oversight will frequently require the ethics function to translate the organisation's ethical values into expectations. There are a number of recurrent elements which provide organisations with an effective way to tackle corporate ethics. These are outlined in the IBE Business Ethics Framework which is based on its definition of business ethics: “the application of ethical values to business behaviour” (see Figure 1).

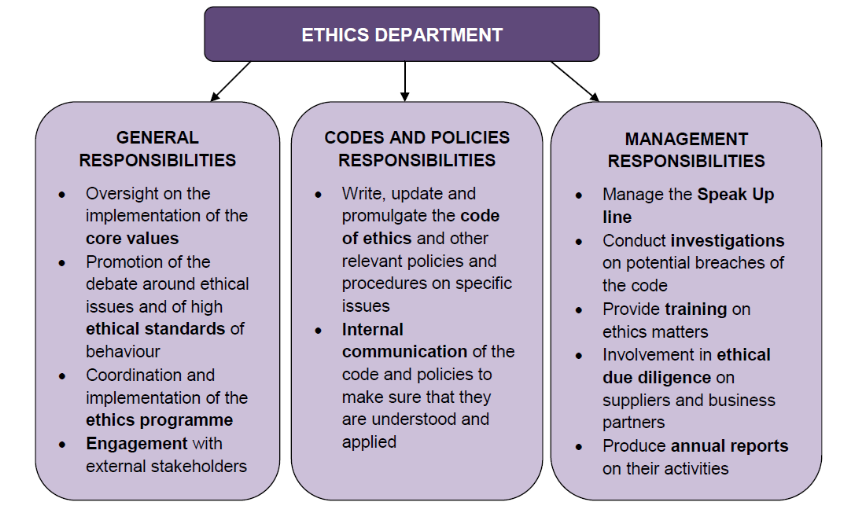

The responsibilities of the ethics function are commonly grouped into three broad areas of responsibility: general responsibilities, code and policy responsibilities and management responsibilities (see Figure 2).

Benefits of an ethics function

An effectively managed ethics function has an important role to play in helping to safeguard an organisation’s reputation, providing guidance to staff and creating a shared and consistent corporate culture.2 According to IBE research, these are the three most common purposes of a company’s ethics programme.3

Figure 1: IBE Business Ethics Framework

Figure 2: Responsibilities of the Ethics Function

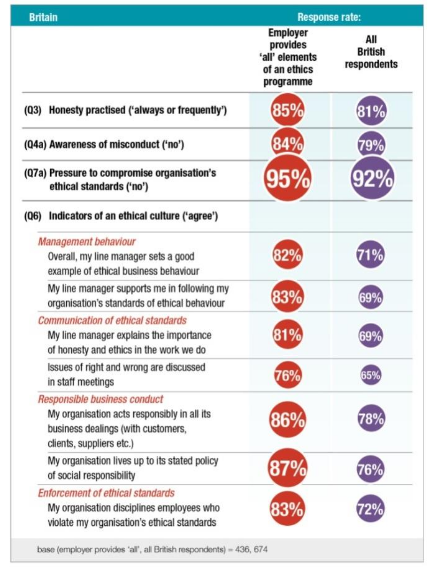

Organisations that offer support to their employees on ethical matters are able to influence their behaviour positively and, as a consequence, the ethical culture of their organisation. The results of the IBE Ethics at Work 2015 survey shows that employee awareness of corporate ethics programmes increases both their ethical awareness and their perception of ethical culture. Employees who indicated that their organisation provided all four common elements of an ethics programme (code, speak up line, advice line and ethics training) were more likely to agree with each of the measured indicators of an ethical culture; they further had a more positive perception of the behaviour observed in their organisation (see Figure 3).4

Figure 3: Benefits of an Ethics Programme

Towards a more useful ethics function

An organisation’s ethics function is often afforded limited resource both in terms of budget and the number of staff. Although some would describe their functions as lean, there are a number of ways in which the ethics function can make best use of its resources and maximise its impact.

Direct access to the board of directors

Ensuring access to the very top of theorganisation is vital for building traction of the ethics function. This works in two ways: first, by having the buy-in of senior leadership – at both executive and board level – the tone is set by those at the top, cascading down through the organisation and played out at different levels. This is widely cited as the greatest enabler of the ethics function.5

Second, getting ethics messages heard in the boardroom is of utmost importance. Many organisations we have been in contract with suggest that being able to report directly to the board, in the absence of executive management, allows for an unfiltered upward flow of information capable of informing decision-making at the highest level.

For some companies, one way to ensure this communication is through dedicated board-level committees. IBE analysis of the Terms of Reference of the 55 companies in the FTSE 350 with board-level committees covering corporate responsibility, sustainability and ethics found that they tend to serve a number of different purposes. However, common themes include the oversight of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. According to the Terms of Reference of a FTSE 100 Bank,

The Committee’s role will cover: brand positioning, culture and values, reputational risk management and all aspects falling within theGroup’s sustainability agenda.6

A substantial majority of these committees (69%) are found to be chaired by an independent Non-Executive Director (NED). The research also revealed that the most common minimum frequency of committee meetings is between two and four times a year.7

Collaborating with other functions

Particularly in organisations where the number of employees dedicated to ethics is limited, many choose to approach the function’s responsibilities in a collaborative manner, utilising the skills, experiences and resources of other departments. This may require close collaboration with subject matter experts or responsible individuals appointed from elsewhere in the business – across both business units and geographic locations. Helpful relationships can be forged with a number of different functions, depending on need. These include internal audit, corporate responsibility, legal, internal communications, compliance and human resources.8 This approach is best summarised by one ethics function head who described the relationship with other functions as “independent but collaborative”.

Adopting an oversight role

Another way of managing the limited resources of an ethics function, whilst also successfully encouraging individual ethical decision making, can be to adopt an oversight role, delegating responsibility for the day-to-day management of ethical issues throughout the business. This can be achieved through empowering managers, supervisors and leaders – thereby delivering the tools to deal with issues locally. In such situations, the ethics function plays the role of resourcing management, providing the capabilities for ethical decision-making. Resources may include management toolkits, training guides and/or decision-making models.9 The ethics function may provide an advice line (or equivalent) where managers, and employees more broadly, can ask questions or raise concerns when faced with uncertainty. This could supplement the organisation’s speak up arrangements.10

Another approach found to be beneficial is the appointment of ethics ambassadors (or equivalent) throughout the business. This position may be full-time but is typically taken on in addition to an employee’s existing day-to-day responsibilities. They can act as the ‘eyes and ears’ of the ethics function, serving as local point of contact for employees and providing a physical presence or ‘face’ for ethics throughout the organisation.11

Communicate clearly

Many organisations are more used to informing rather than communicating which can pose a challenge for an ethics function. Communications from the ethics function should not be as simple as informing employees about facts, figures and procedures and checking that they are compliant. Instead, the use of true experience is found to be an effective way of getting messages across.

Employees will communicate informal messages about ethics in the organisation regardless of the internal communications strategy, whether they realise they are doing so or not. When defining the key messages to come from the ethics function, it is important to be clear, inclusive and accessible. Common messages from ethics functions will include a call to action, whether to speak up, read the code, or live the values. However, a common mistake is to communicate in one direction, in a way which is commanding or negative, rather than engaging employees in a constructive discussion.

Poster campaigns, special events (such as ethics days), banners on the company intranet site, internal social media platforms and videos are all common ways in which positive, engaging messages can be shared.12

Monitor and measure performance

To maximise the function’s effectiveness, a robust reporting framework should demonstrate how the ethics function contributes to the organisation’s overarching objectives. Defining clear measures of success by making use of metrics will help to build supportwithin the organisation. It will also help to identify the parts of the programme which require more attention. Such metrics can also provide assurances to the board.However, deciphering meaningful metrics remains a challenge. Reporting on contacts and cases raised through the organisation’s speak up (whistleblowing) systems can provide valuable insights. This is particularly true of information relevant to investigations into misconduct.

Other data sources which can be reported on include feedback from employee surveys or ethics-focused training courses; information gathered in due-diligence of potential suppliers or by the internal audit function as part of its assurance programme; numbers of breaches of the code; employee turnover figures; exit interview data; main achievements and improvements introduced, as well as steps taken to mitigate the most prominent ethical risks – even cases where suggested action has been absent.13

As discussed above, there are numerous internal communication channels through which these can be disseminated to different internal stakeholder groups. The ethics function may also wish to share some of this information externally. The scope of narrative reporting is continuously increasing. It presents an opportunity for the annual report and/or the corporate responsibility report to raise awareness throughout the organisation of how seriously the board takes ethical issues and the effectiveness of the ethics function.14 This notion is supported by Section 172 of the Companies Act which sets out a duty to promote the success of the company, enjoining directors to report on stakeholder interests with a long-term outlook.15

The culture of an organisation is shaped by its values and their reflection in employees’ behaviour. It is important, therefore, that every employee appreciates his/her individual responsibility for promoting high ethical standards through living up to the organisation’s values. The UK Corporate Governance Code16 asserts a crucial role for the board of directors – it is essential that they set the tone and actively assure themselves that the organisation’s values are embedded effectively.

Foremost, the presence of a dedicated ethics function or department serves to support these responsibilities, ensuring their practical impact. Second, where gaps are identified, a dedicated team already exists to assist in overcoming such lapses.

1 For the purpose of this briefing, the shorthand ‘ethics function’ is used to cover a variety of terms given to functions within organisations who are tasked with (amongst other priorities) embedding the organisation’s values to reflect its culture and behaviours.

2 IBE Report (2014) The Role and Effectiveness of Ethics and Compliance Practitioners – the research uncovered three distinct ‘domains of activity’ – custodianship, advocacy and innovation – representing different interpretations of the E&C role.

3 IBE Survey (2013) Corporate Ethics Policies and Programmes

4 IBE Survey (2015) Ethics at Work 2015: survey of employees – main findings and themes

5 IBE Core Series (2005) Setting the Tone: ethical business leadership

6 IBE Survey (2016) Culture by Committee: the pros and cons

7 Ibid

8 The IBE has considered the interaction between the ethics function and other departments in the following publications: IBE Briefing (2014) Collaboration Between the Ethics Function and HR,IBE Board Briefing (2015) Checking Culture: a new role for internal auditand IBE Good Practice Guide (2015): Communicating Ethical Values Internally

9 See IBE Good Practice Guide (2011): Ethics in Decision-Making

10 See IBE Good Practice Guide (2007): Speak Up Procedures

11 See IBE Good Practice Guide (2010): Ethics Ambassadors

12 IBE Good Practice Guide (2015): Communicating Ethical Values Internally

13 IBE Core Series (2006) Living Up To Our Values: developing ethical assurance

14 IBE Briefing (2014) Business Ethics in Corporate Reporting

15 Companies Act 2006 Section 172

16 Financial Reporting Council (2016) The UK Corporate Governance Code