Tags: Decision-making, Health, safety & security, Data privacy, Cyber security

What are the wider ethical implications of GDPR? How can an organisation’s values be embedded and monitored so that the new regulation becomes a measure of those, rather than simply a set of compliance rules that must be ticked off?

A regular conversation the Institute of Business Ethics holds with its supporters and beyond concerns the ever increasing need to transform value words into meaningful behaviours. How do fairness, openness, confidentiality and other organisational values manifest themselves in different parts of business practices? To this end, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), enforceable on 25 May 2018, could be viewed as a gift; it has provided not just an opportunity for fresh thinking, but a challenge on how best to make ethical values integral to the psyche and behaviour of all in the organisational group. Unless the gap between theory and practice is closed, the risk of reliance on structures and systems is heightened.

Where there are exercises and systems, there is programming and choice. Thus, in spite of much of the literature around it, GDPR is not just a set of specific compliance rules. What it does do is highlight the importance of applying ethical values to decision-making, establishing processes in a transparent manner with training and monitoring employees on the associated behaviours. Whilst organisations scurry to assess whether they tick all the boxes, the much greater issue will be whether all employees are sufficiently aware of the crucial role they must play in supporting the implementation of improved privacy measures. Where both processes and people are involved, we invite ethical risks. Those can only be mitigated by focusing on choice, attitude and behaviour. The premise of GDPR is accountability. Therefore it must be approached with a cultural mindset of transparency and openness.

GDPR – what, when, why, but how?

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) recognises the need to update legislation appropriate to the digital age, thereby setting out articles for the legal capture, use and transition of personal data through organisations. Replacing the existing Data Protection Act, it represents

the most important change in data privacy regulation in 20 years.2

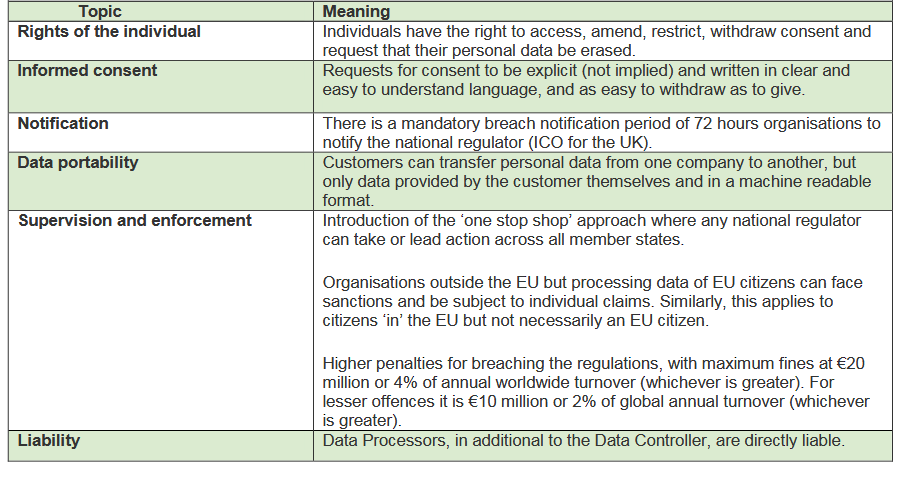

By introducing some key changes and updates, it seeks to give back control to the individual over how organisations use their personal data and to harmonise privacy laws across Europe (the legislation will form part of the Great Repeal Act in the UK so will still apply after Brexit). Table 1 sets out the key changes.

Table 1 - GDPR: points of clarity

As a piece of legislation, GDPR will be instantly enforceable, helping to drive the strong focus around its arrival date. The changes are significant and have certainly warranted the considerable attention surrounding it. Getting it wrong could mean significant fines, negative publicity, reputational and brand damage, loss of trust, legal action and regulatory enforcement.

However, accommodating the changes should not be driven by fear of consequence. Rather, organisations might consider how well their values behaviour supports areas of business practice and how scenarios might play out that will lead to their systems and procedures facing challenge. This might come from an external individual requesting that their data be deleted or moved, or a hacker trying to gain personal data illegally. It might also come from within – an aggrieved colleague who performs a Subject Access Request (SAR) following the conclusion of a Speak Up investigation.

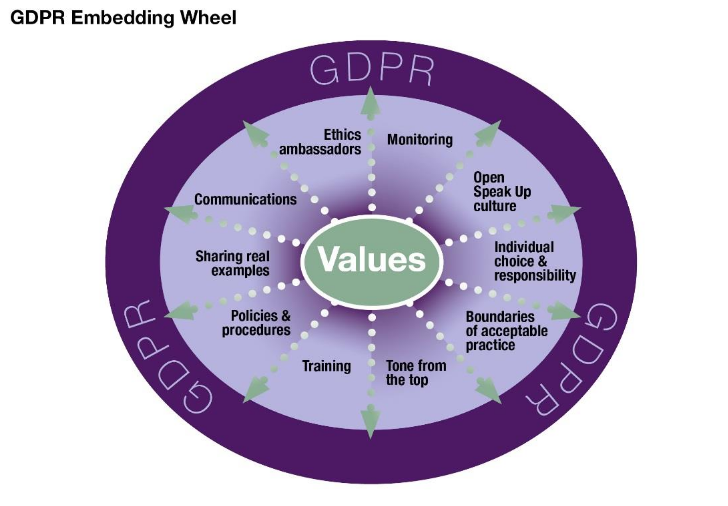

Whatever the requests around personal data, organisations are reliant on their own staff to know, understand and commit to appropriate behaviours and values. It is that which will allow choices to be made that will serve to protect the individual and the organisation, as well as make fluid the activities that recognise the governing laws. This is why an ethical culture is so important: how values are communicated within an organisation; how they are demonstrated by leadership; and how they are embodied in day-to-day working relationships by all employees. Some methods by which that can be achieved are identified in the GDPR Embedding Wheel below and throughout this discussion.

Separating Ethics and Compliance3

The IBE refers to ethics as ‘starting where the law ends’; an indicator towards the need for the most rigorous physical systems and rules to be backed up by an understanding of what might affect their working implementation. More than that, it requires individual responsibility. In his recent book4 Nassim Taleb points out that ‘laws come and go; the ethics stays’. When the new laws arrive, what, or more likely who, ensures they can be accommodated?

The approach that some organisations seem to have taken is to have prepared for the GDPR deadline in order to demonstrate compliance with its requirements. This level of thinking might be viewed as too short-term and narrow; GDPR does not represent a one-off happening. Others recognise that the deadline is not something to observe alone. Some even realise that it requires a greater strategy in terms of data protection and privacy, of which GDPR forms only a part.5 More than that, there is a much wider state that should be recognised and considered – the ethical culture.

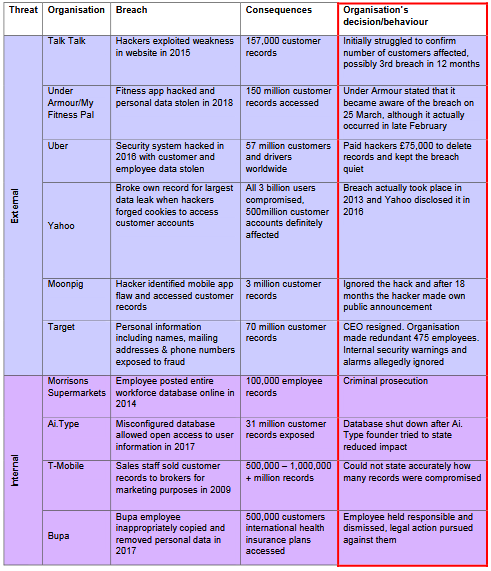

We have become aware from numerous recent examples that a lack of consideration for how values inform decision-making can lead to organisational lapses and failures. These can impact business, colleagues and society. Some of these relate to personal data breaches, shown in Table 2.

It is the fourth column – the consequences – that might attract an organisation’s eyes initially. However, the IBE would encourage focus on the first and final columns. The first indicates that GDPR breaches do not arrive from external threats only. ‘People risk’ within an organisation should be awarded equal attention. Securing physical systems fully still cannot mitigate a poorly trained individual with a desire or capacity to act against the values. A recent EY Survey6 showed that 55% of 1735 respondents rated ‘careless or unaware employees’ as the highest or second highest vulnerability in cyber risk.

The final column prompts organisations to ask key questions around the role an ethical culture plays in preventing breaches before they occur, as shown in Box 1.

This makes clear that paying attention to laws and rules alone is not sufficient. Only in considering questions like those above can an organisation accurately begin to assess to what extent they are prepared and able to accommodate the new regulation.

Table 2: Recent personal data breaches7 8

|

Building awareness to maintain trust

The GDPR restores control to the individual. A key point is that individuals will have the right to object to their personal data being processed unless the organisation can demonstrate compelling legitimate grounds for the processing which override the interests, rights and freedoms of the data subject or for the establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims. This means it is particularly important that organisations have in place a strategy for allowing transparency up front regarding their processes and procedures. That is, how are we going to maintain privacy of personal data? It is crucial that all individuals are aware of what their rolemight be in protecting the value of this data.

|

Consider if...

|

Early planning is relevant to all parts of business activity that holds personal data, together with ongoing reviews. In the above example, whose responsibility would it be to ensure that this level of transparency and security is achieved? Is it a risk manager who is a key business enabler; a functional lead, whose open, visible leadership and articulation of the values is crucial; a lawyer whose application of expert knowledge will ensure contractual principles are secure? Where does the accountability lie if something goes wrong or if there is a breach? A 3rd party will need to have a formal process to inform you that they believe there is a breach and what you will need to report. If the 72 hour deadline isn’t met, you are responsible as data controller. If penalties are then applied, how have you articulated what would be fair to assign to the 3rd party? If a data processor has a single data breach but the data is on multiple records, the fine might not be for one breach but for multiple breaches under GDPR depending on the severity and/or risk to data subjects’ rights.

Establishing the boundaries and clarity of processes and procedures early on, to all parties concerned, is vital in achieving strong and fair outcomes. GDPR is personal; it affects everyone.

|

Consider if...

|

With questions like those in Box 3, there are multiple ways that an organisation can quickly lose trust if the approach of all involved is not applied appropriately. In large organisations, personal data may be held on hundreds of different systems across multiple functional areas. The need to have a streamlined process for the management of personal data becomes even more complex and challenging. A breach that occurs in one jurisdiction alone, or primarily, could affect the reputation of the whole group. In a large or small business, do all employees know how to manage risk to prevent breaches, but also respond appropriately if required?

Ultimately, is the entire organisation trained on how to deliver work according to the values such that all members behave to appropriate and aligned standards? However large or small your organisation, whatever stage you have reached in terms of preparing to accommodate the new regulation, the holistic and comprehensive approach required has to start at the top.

Tone from the top

The view, input, visibility and management by business leaders are crucial to the ultimate success of an organisation. Setting tone from the top is important for all aspects of organisational strategy, not a selection:

GDPR is only part of an enterprise’s overall strategy for data protection and privacy, and this strategy is ongoing and ever-evolving as circumstances arise.9

Symantec research (2016), reported in I-Scoop, revealed that only 14% think GDPR is the responsibility of everyone in an organisation to make sure data is protected.10 Business leaders have an essential role to play in building trust into the process. Being aware of the laws, the risks they bring and talking about how those will impact choices and decision-making, is one aspect. Empowering all staff to know what can/cannot happen and that it is everyone’s business and responsibility requires a cross-departmental strategy. Demonstrating a level of courage in talking about mistakes and lessons learned is as important since mistakes are best addressed quickly and transparently.

Going back to the final column in Table 2, how can customers, clients and other stakeholders trust that they will be informed immediately of a breach, if severe enough to warrant that? Have the business leaders informed those with such responsibilities in the organisation regarding the appropriate level of openness?11

This calls for increased transparency in senior level decision making: decisions taken at this level and how they flow through the organisation and ensure that not only security, HR, legal and risk managers are aware, but all employees in all parts of the business. Table 2 clearly demonstrates that responsibility and accountability sits with the business leaders. Therefore transparency around their decisions becomes crucial and requires change at the organisational level.12 In the very unfortunate event of a breach, it will be imperative for organisations to demonstrate that they had made all efforts possible to prevent it happening in the first place. As reported in The Privacy Advisor, the main focus of the Information Commissioner's Office will be on transparency, control and accountability.13 This means they will be assessing the cultural awareness of the people. This cannot be achieved if organisations haven’t even considered strategy at the Board level and who is responsible for execution.14 For those further ahead, business leaders need to remain informed and make sure monitoring is reported back to them in order to allow them to reinforce the values-led behaviours.

|

Consider if...

|

In Box 4, looking at some of the risks in the Speak Up process, it becomes even clearer why personal data is the business of everyone, and that an organisational approach to attitude, training and communication is crucial in recognising its value and protecting it.

Establishing the boundaries and standards

What policies and procedures are in place to protect the ethical standards of the Speak up process? How will these help to ensure that personal data is used appropriately? The policies that govern the process must provide clarity on the organisation’s approach: what should people expect within the process and what can they do if they are not satisfied. For example, if an individual is not content with the process or outcomes, whom can they contact? These documents should provide detail that allows individuals to feel confident that their personal data is managed with consistency and rigour. For example, what does confidentiality and anonymity really mean in such a process? For those involved in a Speak Up investigation, it is not enough to simply acknowledge that the information must not be shared beyond appropriate people and that an individual has the option to remain anonymous. It is the how that matters.

For example, if a reporter needs to discuss the emotional distress surrounding their concern with a friend, colleague or family member, they might to do so. It is better to share emotional stress and avoid outcomes like ill health than to completely limit conversations. However, that means they require specific guidance on what level of detail can be discussed, how to frame such conversations and advice on who to choose to speak to. Will that third party be sufficiently aware and capable such that they don’t then compromise the process by sharing personal data? How can employees easily identify which individual is the Data Protection Officer with responsibilities aligned to the Speak Up process? Will they be told that they have a right to complain to the Information Commissioner’s Office if they think there is a problem?

Will an organisation be responsible about the use of pseudonyms - where an identity is replaced by a number or project name so as to strengthen the confidentiality and anonymity during the investigation process? Whilst this is a positive measure for an organisation, the flip side of this is that should an individual want to perform a subject access request, they will need to know to request all identifiers attached to their name and not just documents with their exact name on.This suggests policies and procedures must be backed up by a comprehensive training and communications programme.

Communication and Training

Communication around individuals that is based on emotion, perception and opinion can be very damaging to individuals and organisations. In the investigations process, what communication is required for all parties involved to build trust? What information will be captured and where from, how will it be stored and transferred, and what will be available to third parties at different times? The earlier people know this, the stronger the outcomes. Training must make the policies and guidance easily accessible. Cultural workshops can support understanding of those and address more specific areas that require awareness; eg in what situation might an employee commit personal information in physical form (email) that will become a future risk? Particularly in large organisations, people cannot meet face to face and must either pick up the phone and hope to get hold of a busy colleague, or, more likely, commit their thoughts to email. Do they know that those emails will become available publicly if a Subject Access Request (SAR) is made?

If a SAR is made and emails are identified as containing inappropriate personal data, the organisation will then be faced with a choice. Release the emails with damaging content that will allow an already upset individual to potentially claim compensation, and consider showing on social media or to the mainstream media, or withhold information to mitigate threats to the organisation’s reputation. Organisations must pass on this information in good faith; they must not apply prejudice and produce all relevant information.

Privacy teams acting alone might be tempted to warn people against committing thoughts to email (to avoid having to release later in the SAR situation). Yet shouldn’t the training advice instead cover what constitutes appropriate communication and responses according to the values such that we don’t need to worry about what is committed to email? Training can then address lessons learned from when relationships break down and result in SARs.

Perhaps GDPR is a prompt to the organisation that it requires a greater focus on a network of ethics ambassadors to ensure key messages and expectations around values are considered more seriously and embedded more widely? How should employees replicate the attitude and cultural expectations set by business leaders?

Investigator training is important. Sometimes investigators are not trained; Speak Up reports can be triaged and sent to subject matter experts to be investigated. A particular focus needs to be placed on training in order to 1) increase the efficacy of the process, and 2) ensure expectations of GDPR are met appropriately, reducing the opportunity for individuals to create risks by making decisions outside the parameters of GDPR.

Choice of the Individual

The IBE encourages organisations in their ethics programme to discuss and explore with employees the justifications and ways that they think, as well as providing a scenario and arriving at the most appropriate choice together. What affects that choice? How do we reason; what do we choose to pay attention to and ignore? This is particularly relevant to GDPR. Are your employees aware of how they make choices and their responsibilities around those? Individuals are not just the victims of data breaches - they can be active participants in the process. In an organisation, just as on social media, the storage, use and transfer of personal data 'isn’t just something that is being done to the public, it is being done by the public'.15

Monitoring Outcomes

How do employees feel supported to do the right thing? What processes exist for monitoring outcomes and celebrating good practice? How is that communicated effectively and transparently such that others learn and benefit?

When an organisation monitors and tracks employees that work for them, they collect personal data about them. Robust recruitment processes will strengthen transparency. However, if an organisation has been building profiles of employees that are not relevant to their job, they are likely to be fined. Similarly, it will become especially important to put measures in place to understand what information is carried forward at the end of an investigation; how report recommendations are monitored and how the individuals communicate their experiences going forward. What personal data needs to be held, what should be deleted? An organisation needs to establish their appetite for this and understand how that sits in relation to the laws and ethical standpoint of the organisation.

Further, if someone does performs a SAR, any previous personal information that has built up about them will need to be released also. GDPR introduces an important change in this regard: organisations will only have one calendar month to process a SAR, instead of the previous 40 days. The timing imposes a need for early planning. What can happen is that a SAR might be sent to the line manager of the respective individual. In Speak Up cases, individuals who contact a Speak Up line may be reporting concerns about their line manager, or have already tried raising the issue with them. A risk arises if the SAR is then sent to that manager.

In the instance of a breach occurring, the introduction of ‘class action’ is particularly important. If a data breach affects multiple individuals, they can act as one group. If business leaders do not establish a cultural tone and approach based on the values, and drive an appropriate awareness and training programme, the likely outcome will be a large collection of upset individuals, grouping together to remind them of that. And, with class action, the cost of getting it wrong will only increase.

1 EU-Lex: Access to European Union Law

3 IBE (2017) Ethics and Compliance Handbook.

4 Taleb, N. (2018) Skin in the Game. Random House.

5 ISACA (2018) Maintaining Data Protection and Privacy Beyond GDPR Implementation.

6 EY (2016) Path to cyber resilience: Sense, resist, react.

7 TechWorld (2018) The most infamous data breaches.

8 ZDNet (2015) Anatomy of the Target data breach: Missed opportunities and lessons learned.

9 Ibid fn 5.

10 I-Scoop (2018) GDPR awareness: a matter of people, culture, leadership and acting now.

11 EU Parliament, Article 34

12 PrivSec Report (2017) GDPR and Board Level Transparency.

13 IAPP (2017) ICO's Wood: GDPR grace period? No way.

14 Ibid fn 10.

15 Huffington Post (2010) Why Transparency and Privacy Should Go Hand in Hand.